Search

Items tagged with: PalmOil

Pileated Gibbon Hylobates pileatus

The charming Pileated Gibbon (Hylobates pileatus) is endangered in Cambodia, Laos. They are threatened by palm oil deforestation. Take action!Palm Oil Detectives

wp.me/pcFhgU-EV?utm_source=mas…

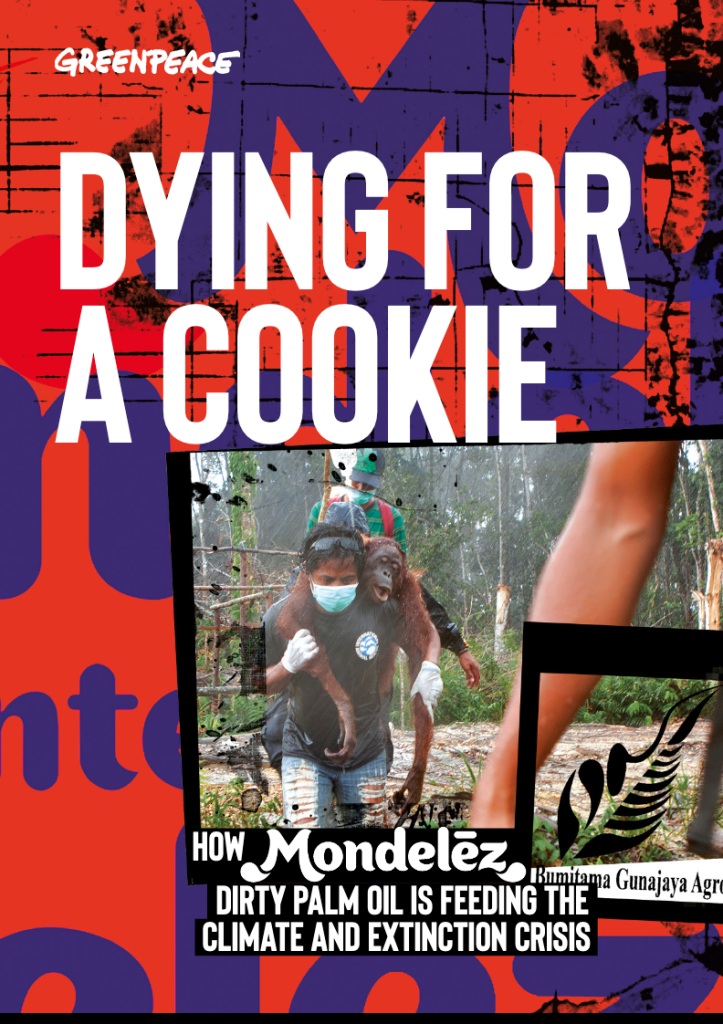

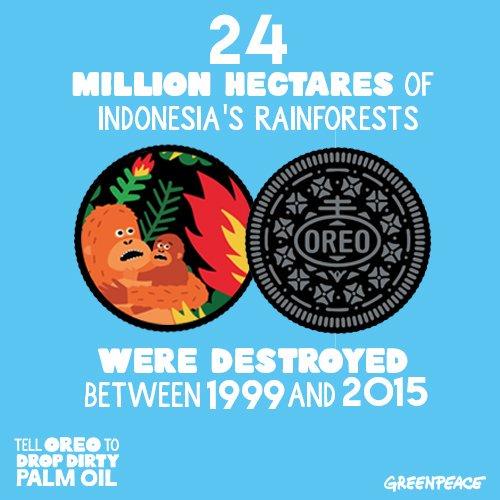

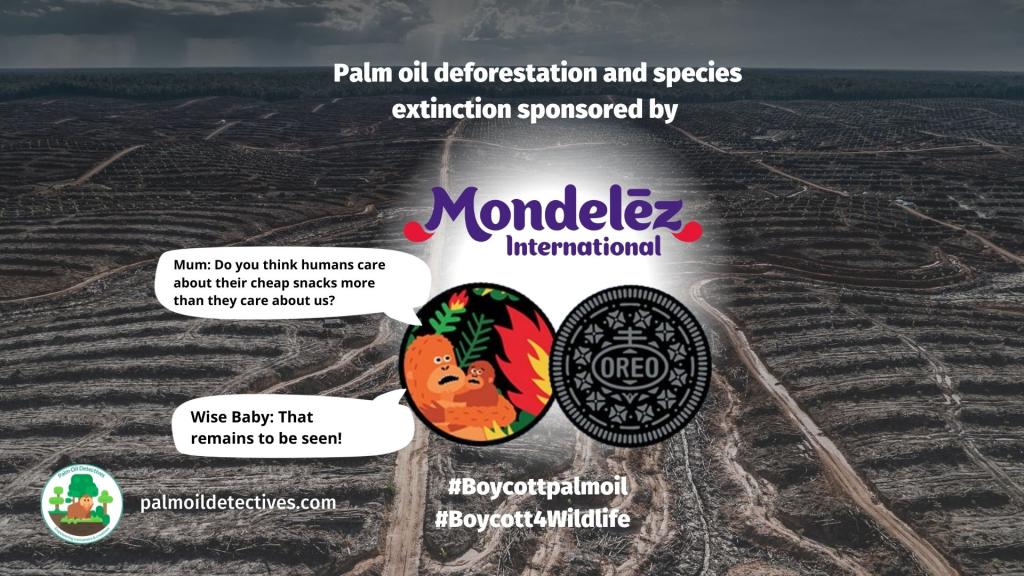

Brands Using Deforestation Palm Oil

These brands have products that contain palm oil sourced from mills that are responsible for the destruction of precious habitats of endangered species. Just in 2020 alone, these brands (along with…Palm Oil Detectives

Nicobar pigeon Caloenas nicobarica

The Nicobar pigeon is the largest pigeon in the world and the closest living relative to the extinct dodo bird. They are famous for their gorgeous iridescent feathers. When threatened they make a p…Palm Oil Detectives

The elegant #Sunda flying #lemur AKA #Colugo can glide 100m through trees 🪽🕊️ in #Sumatra #Kalimantan and #Borneo. Totally reliant on trees, #palmoil is a major threat to them 😿 Fight back and🌴🩸🔥☠️🧐🚫 #Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife

palmoildetectives.com/2026/02/…

Sunda Flying Lemur Galeopterus variegatus

Sunda flying lemurs AKA Malayan colugos rely on ancient forests to survive, despite being skilful gliders, palm oil is a major threat, boycott palm oil!Palm Oil Detectives

Philippine Sailfin Lizard Hydrosaurus pustulatus

Stunning bright coloured Philippine sailfin lizards are becoming more and more rare from palm oil deforestation across their range in #WestPapua #Philippines and eastern #Indonesia. They are also t…Palm Oil Detectives

palmoildetectives.com/2021/01/…

When you shop #BoycottPalmOil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect.bsky.social palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/…

Johnson & Johnson

Global mega-brand Johnson & Johnson have issued a position statement on palm oil in 2020. ‘At Johnson & Johnson, we are committed to doing our part to address the unsustainable rate o…Palm Oil Detectives

Sumatra’s flood crisis: How deforestation turned a cyclonic storm into a likely recurring tragedy

Extreme rain wasn’t the only cause of Sumatra’s deadly floods. Years of forest loss, eroded soils, and weakened watersheds turned a storm into a tragedy — one that could repeat.The Conversation

Marbled Cat Pardofelis marmorata

Marbled Cat Pardofelis marmorata IUCN Status: Near Threatened Location: India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia (Sumatra, Borneo), China (Y…Palm Oil Detectives

Black-spotted Cuscus Spilocuscus rufoniger

The black-spotted cuscus Spilocuscus rufoniger is one of the most striking and rare marsupials in the world. Known for their soft fur with irregular black spots on a reddish or cream background, th…Palm Oil Detectives

Procter & Gamble

Despite decades of promises to end deforestation for palm oil Procter & Gamble or (P&G as they are also known) have continued sourcing palm oil that causes ecocide, indigenous landgrabbing,…Palm Oil Detectives

The ultra-processed foods problem is driven by commercial interests, not individual weakness. Here’s how to fix it

Without policy action and a coordinated global response, ultra-processed foods will continue to rise in human diets, harming health, economies. It’s time to act.The Conversation

palmoildetectives.com/2021/01/…

palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/…

‘Magical’ galaxy frogs disappear after reports of photographers destroying their habitats

Researcher in Kerala rainforest sounds alarm after being told frogs had died after being handled by humansIsaaq Tomkins (The Guardian)

palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/…

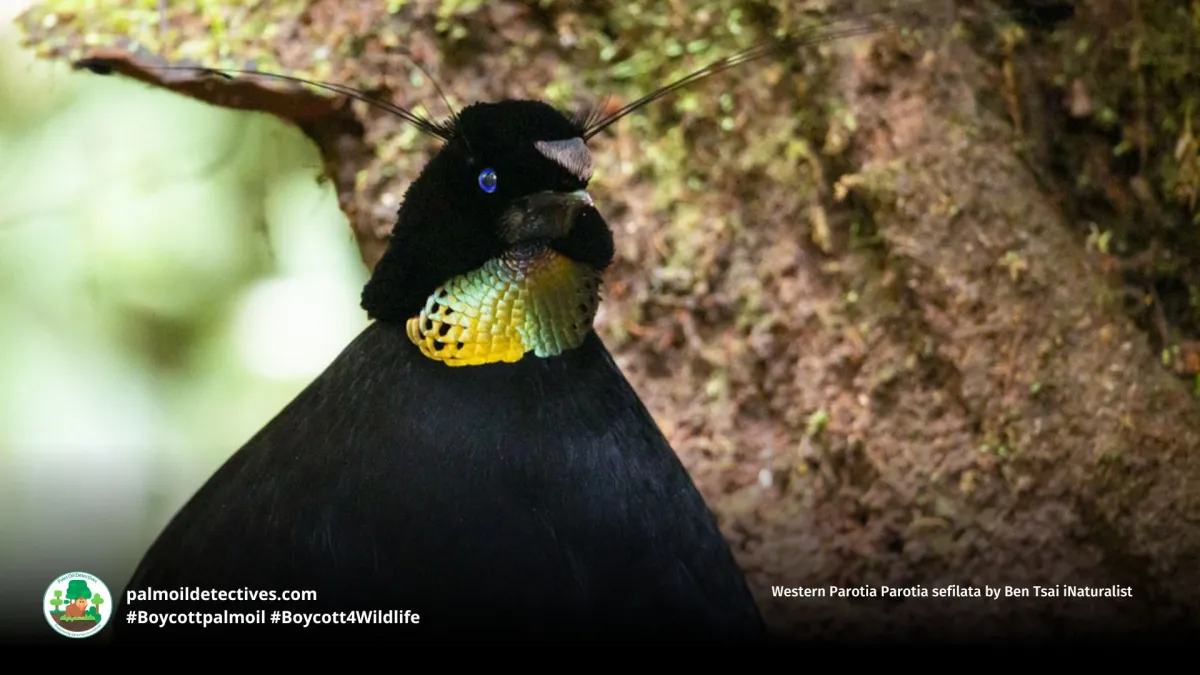

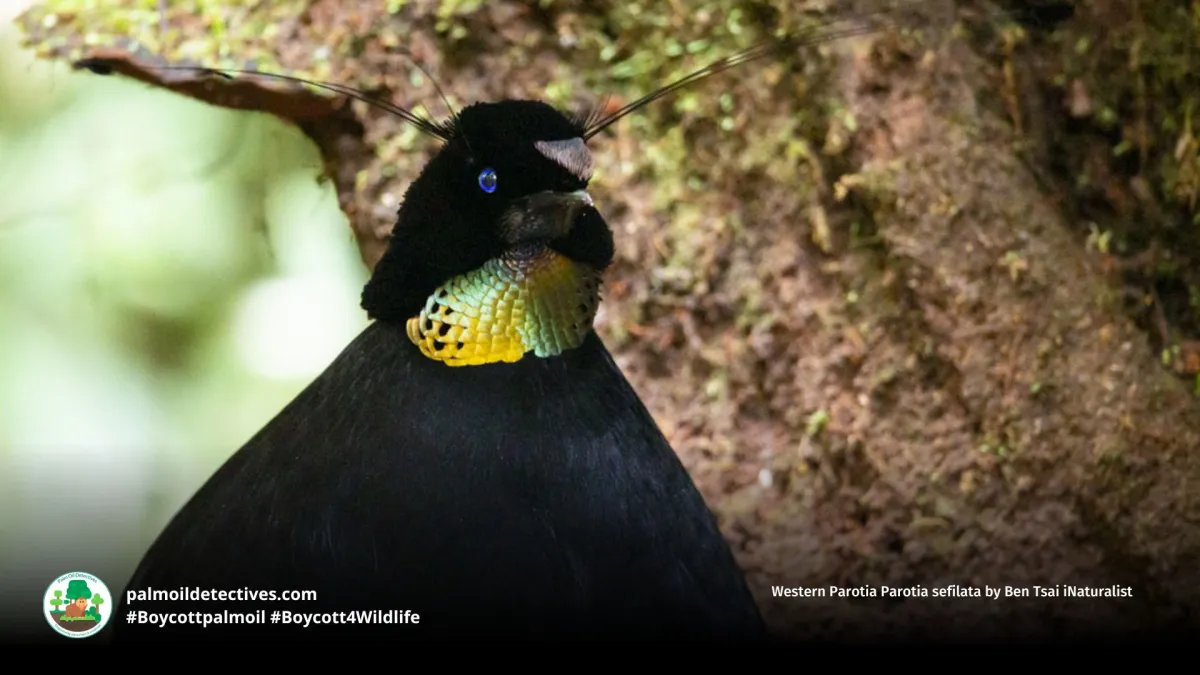

Magnificent Bird of Paradise Cicinnurus magnificus

Meet the Magnificent Bird-of-Paradise, a dazzling, theatrical bird from New Guinea’s forests. Their vibrant courtship dances must be protected from palm oil!Palm Oil Detectives

Palm Oil Free Chocolate, Candy and Confectionery

Buying chocolate, candy or lollies as a gift or just want to indulge yourself? Then enjoy your chocolate fix without eating rainforest-destroying palm oil! If you are ever in doubt look for the pre…Palm Oil Detectives

Known locally as #Kalong the Malayan #FlyingFox of #Malaysia #Indonesia has a bad reputation but plays an outsized role in keeping #rainforests alive. #Endangered by #palmoil. Use your wallet as a weapon 🌴⛔️#Boycottpalmoil #Boycott4Wildlife @palmoildetect.bsky.social@bsky.brid.gy youtu.be/_GG_fBE_8Io

UK links to human rights abuses scrutinised

Campaigners speak out on the need to hold UK companies to account for abuses.The Ecologist

Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris

Intelligent and social Irrawaddy dolphins, also known as the Mahakam River dolphins or Ayeyarwady river #dolphins have endearing faces. Only 90 to 300 are estimated to be left living in the wild. T…Palm Oil Detectives

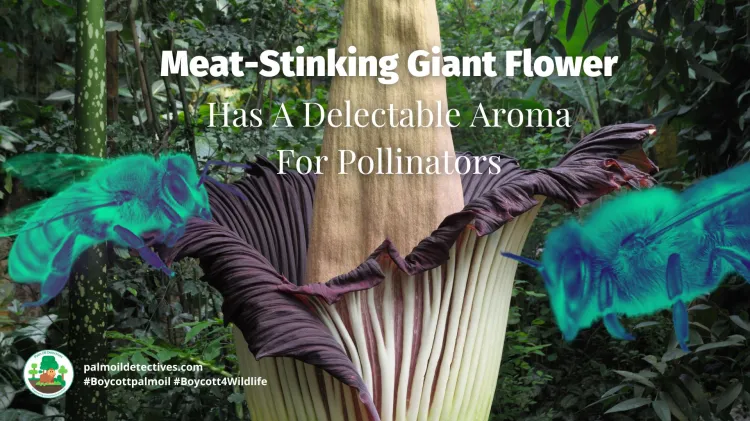

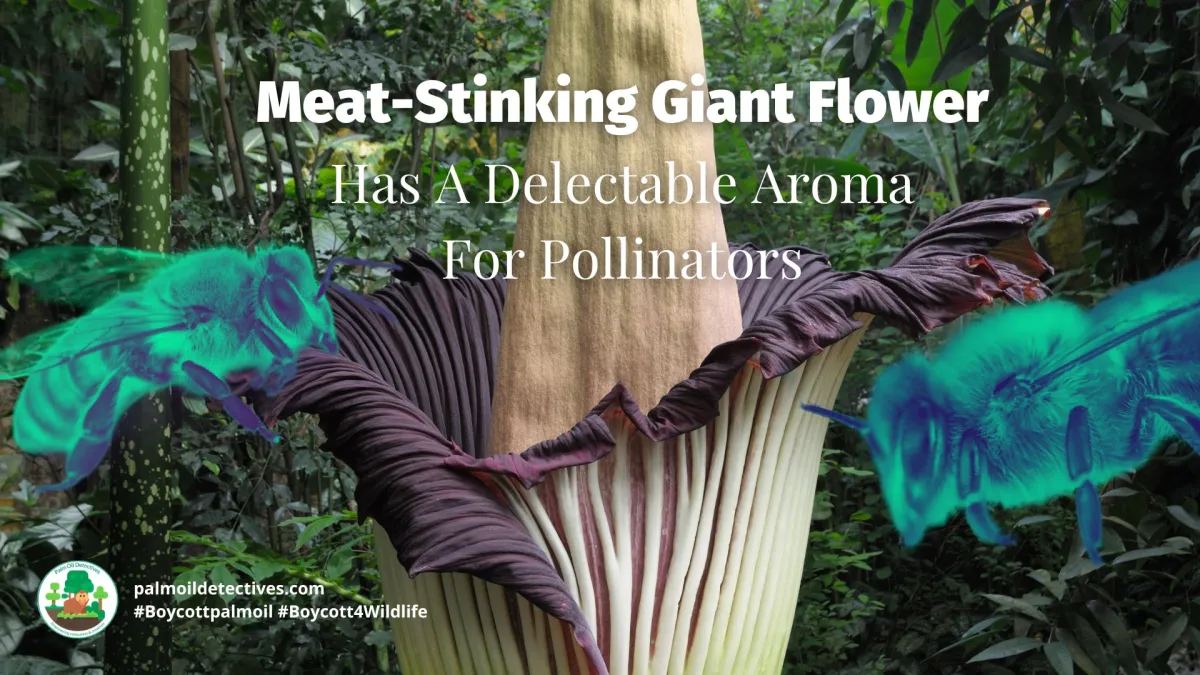

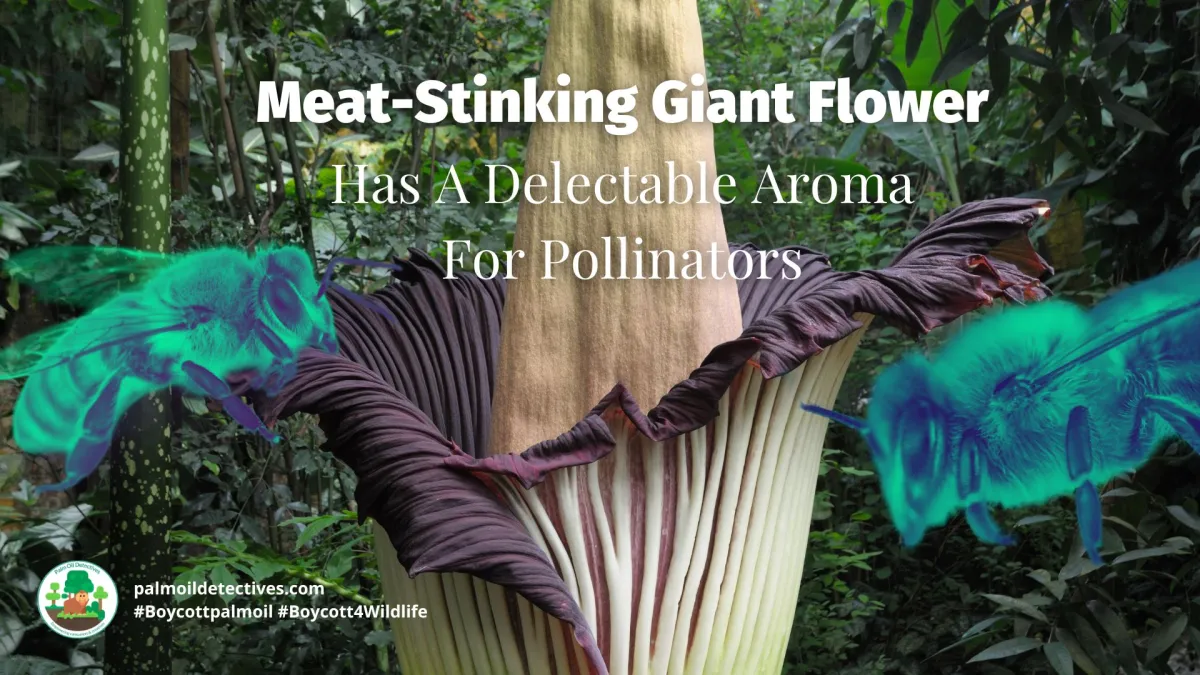

Meat-Stinking Giant Flower Has A Delectable Aroma For Pollinators

Titan Arum AKA ‘Corpse Flowers’ is famous for its repulsive meat smell. Palm oil agriculture is a massive threat to these rare stinky plants. Take action!Palm Oil Detectives

Wallace’s Flying Frog Rhacophorus nigropalmatus

The elusive and visually stunning Wallace’s Flying #Frog are known for their mysterious nature and their ability to take flight and glide through the air like dancers. They reveal themselves …Palm Oil Detectives

palmoildetectives.com/2024/05/…

Magnificent Bird of Paradise Cicinnurus magnificus

Meet the Magnificent Bird-of-Paradise, a dazzling, theatrical bird from New Guinea’s forests. Their vibrant courtship dances must be protected from palm oil!Palm Oil Detectives

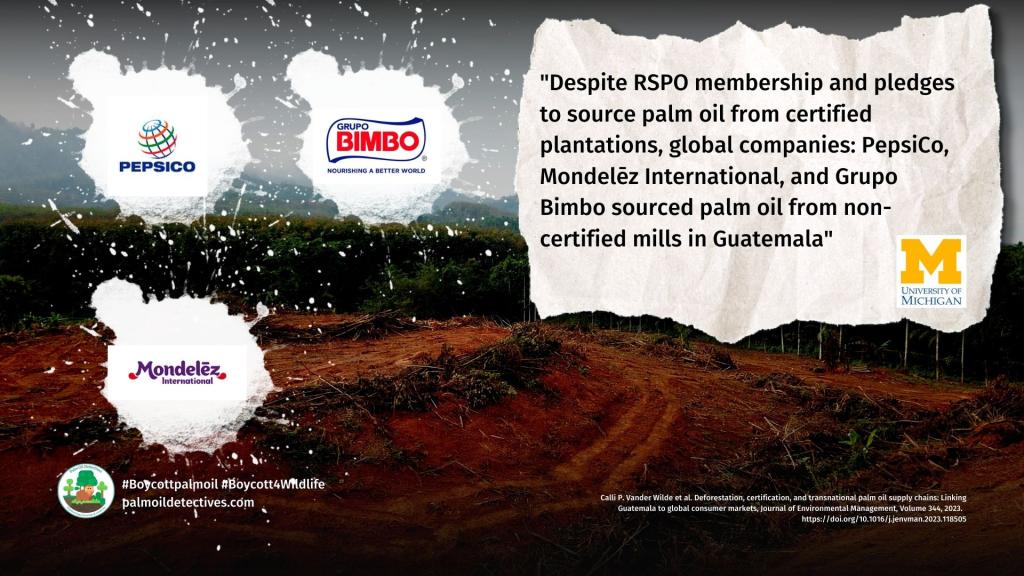

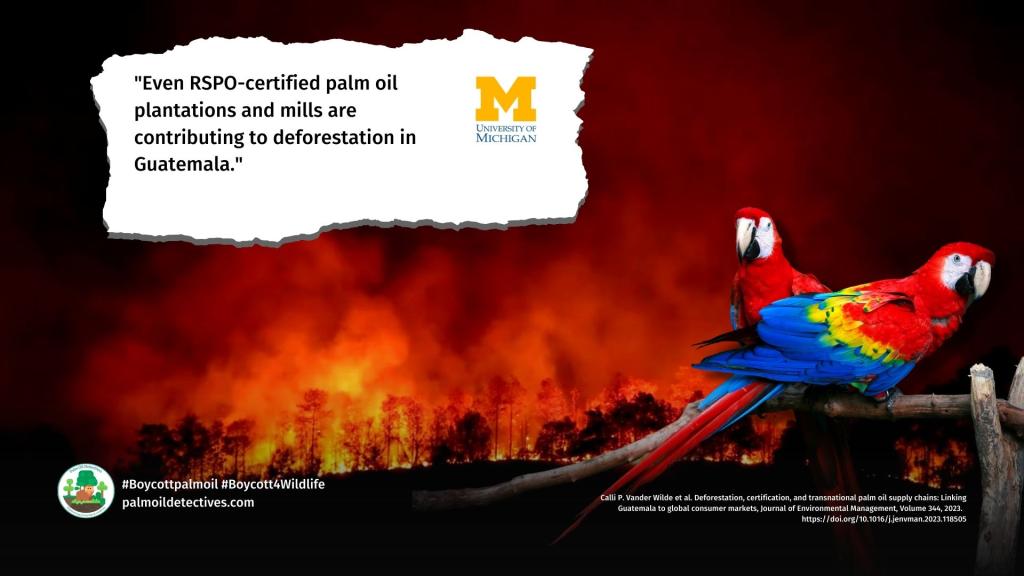

Snack giant PepsiCo allegedly sourced “sustainable” palm oil from razed Indigenous land in Peru

PepsiCo’s supply chain is linked to environmental and human rights violations in Peru, involving Amazon deforestation and Indigenous land invasion. For three years, palm oil from deforested S…Palm Oil Detectives

Sumatran Tiger Panthera tigris sondaica

The Sumatran tiger Panthera tigris sondaica is a critically endangered big cat, with less than 600 of their species alive in the wild today. Once living in Java and Bali, they are now only found in…Palm Oil Detectives

Titan arum

Better known as the corpse flower, the titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) is one of the smelliest plants in the world. It smells like rotten flesh when in bloom to attract flies which pollinate the plant.www.kew.org

Meat-Stinking Giant Flower Has A Delectable Aroma For Pollinators

Meat-Stinking Giant Flower Has A Delectable Aroma For Pollinators