Search

Items tagged with: palmoil

Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris

Intelligent and social Irrawaddy dolphins, also known as the Mahakam River dolphins or Ayeyarwady river #dolphins have endearing faces. Only 90 to 300 are estimated to be left living in the wild. T…Palm Oil Detectives

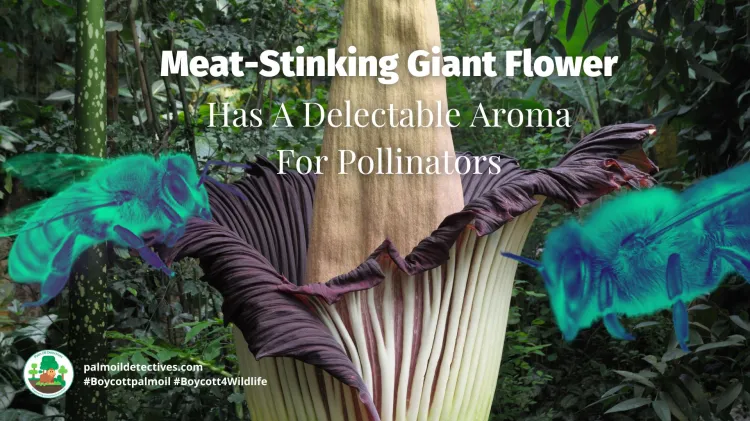

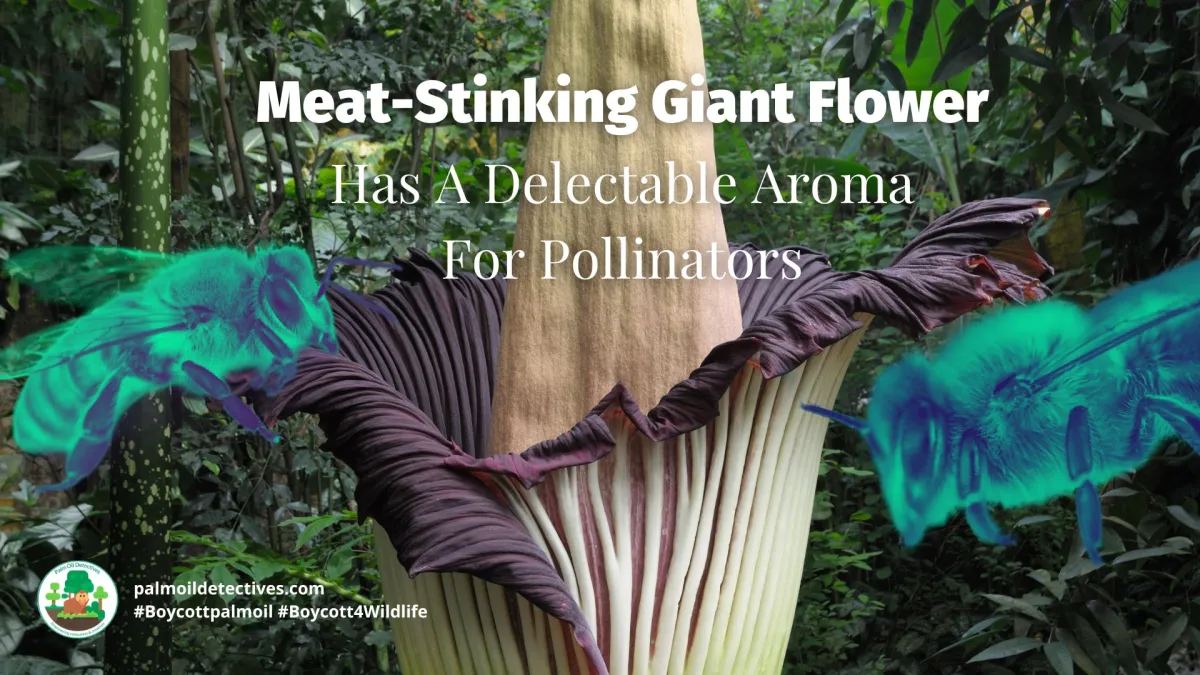

Meat-Stinking Giant Flower Has A Delectable Aroma For Pollinators

Titan Arum AKA ‘Corpse Flowers’ is famous for its repulsive meat smell. Palm oil agriculture is a massive threat to these rare stinky plants. Take action!Palm Oil Detectives

Wallace’s Flying Frog Rhacophorus nigropalmatus

The elusive and visually stunning Wallace’s Flying #Frog are known for their mysterious nature and their ability to take flight and glide through the air like dancers. They reveal themselves …Palm Oil Detectives

palmoildetectives.com/2024/05/…

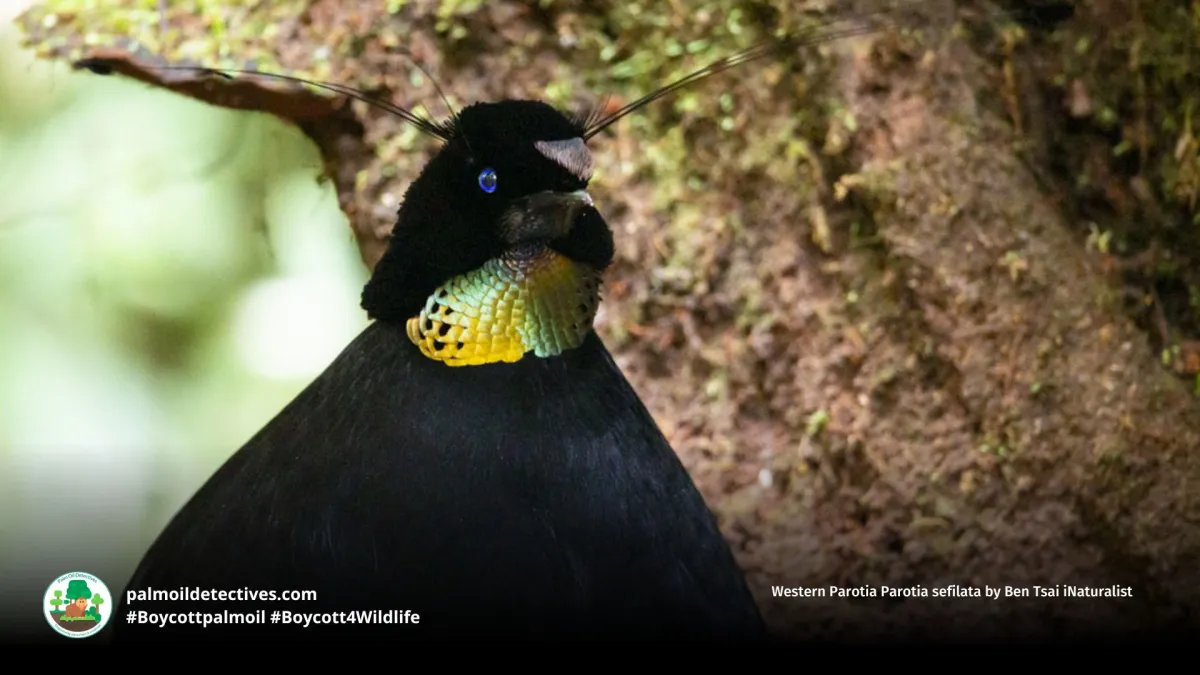

Magnificent Bird of Paradise Cicinnurus magnificus

Meet the Magnificent Bird-of-Paradise, a dazzling, theatrical bird from New Guinea’s forests. Their vibrant courtship dances must be protected from palm oil!Palm Oil Detectives

Snack giant PepsiCo allegedly sourced “sustainable” palm oil from razed Indigenous land in Peru

PepsiCo’s supply chain is linked to environmental and human rights violations in Peru, involving Amazon deforestation and Indigenous land invasion. For three years, palm oil from deforested S…Palm Oil Detectives

Sumatran Tiger Panthera tigris sondaica

The Sumatran tiger Panthera tigris sondaica is a critically endangered big cat, with less than 600 of their species alive in the wild today. Once living in Java and Bali, they are now only found in…Palm Oil Detectives

Titan arum

Better known as the corpse flower, the titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) is one of the smelliest plants in the world. It smells like rotten flesh when in bloom to attract flies which pollinate the plant.www.kew.org

Palm Oil Free Cleaning Products

Clean your home without palm oil rainforest destruction. Learn how to spot hidden palm oil in cleaning products and find brands that are palm oil-freePalm Oil Detectives

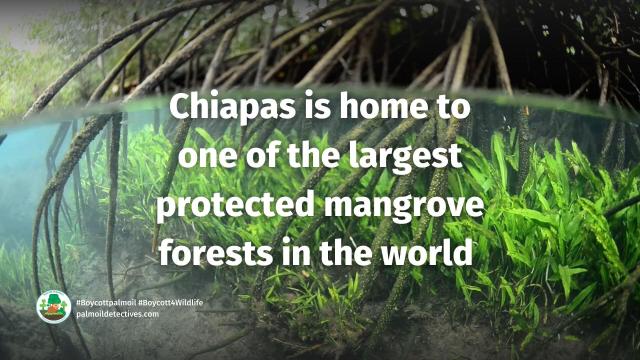

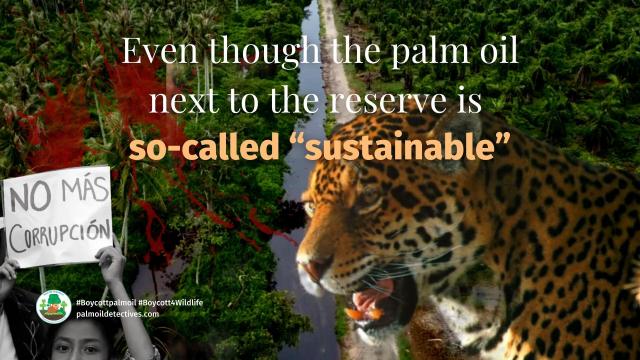

Palm Oil Greenwashing Poised to Destroy Protected Biosphere in Chiapas, Mexico

Situated on Mexico’s lush and biodiverse Pacific coast is La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve – One of Mexico’s most spectacular natural treasures. Now the government and palm oil business…Palm Oil Detectives

Colgate-Palmolive

Despite global retail giant Colgate-Palmolive forming a coalition with other brands in 2020, virtue-signalling that they will stop all deforestation, they continue to do this – destroying rai…Palm Oil Detectives

The vanishing pharmacy: How climate change is reshaping traditional medicine

Gyatso Bista remembers the sacks of kutki. As a child learning to become a healer in Nepal’s kingdom of Lo Manthang, Bista would watch as heaps of the bitter-tasting herb, prized for treating fever, coughs and liver problems, arrived on horseback fro…Latoya Abulu (Mongabay)

wp.me/pcFhgU-72o?utm_source=ma…

Lion-tailed Macaque Macaca silenus

Lion-tailed macaques hold the title of one of the smallest macaque species in the world and sport a majestic lion-esque mane of hair. They exclusively call the Western Ghats in India their home. Th…Palm Oil Detectives

Blue-streaked Lory Eos reticulata

Brilliantly coloured and full of energy, the Blue-streaked Lory (Eos reticulata) is a striking and unique #parrot living in the forests of the Banda Sea Islands, #Indonesia. Their scarlet plumage i…Palm Oil Detectives

Sulawesi Babirusa Babyrousa celebensis

The Sulawesi Babirusa also known as the North Sulawesi Babirusa are wild pigs are found on Sulawesi Island along with nearby islands Lembeh, Buton, and Muna in #Indonesia. They have a mottled grey-…Palm Oil Detectives

palmoildetectives.com/2021/02/…

UN human rights mechanisms urge Guatemala to end forced evictions, protect land rights defenders - ISHR

From 14 to 25 July, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, Balakrishnan Rajagopal, conducted an official visit to Guatemala - only theUlises Quero (ISHR)

Brazilian three-banded armadillo Tolypeutes tricinctus

The Brazilian three-banded #armadillo Tolypeutes tricinctus, known as “tatu-bola” in Portuguese, is a rare and unique species native to #Brazil. With the ability to roll into a near-imp…Palm Oil Detectives

Quince Monitor (Banggai Island Monitor) Varanus melinus

The Quince Monitor Varanus melinus get their name from the spectacular bright yellow of their skin. This is a rare and elusive species of #monitor #lizard that lives in only one location in #Indone…Palm Oil Detectives

palmoildetectives.com/2022/12/…

Palm Oil Free Sunscreens & Insect Repellent

Protect yourself from the #sun 🌞⛱️🌻 while protecting 1000’s of #animals 🦧🦜🪲🦏🐘 from #palmoil #ecocide. Reject #beauty brands like #Loreal and Avon and find #PalmOilFree #Sunscreen. Fight back …Palm Oil Detectives

Chimpanzees once helped African rainforests recover from a major collapse

Most people probably think that the rainforest of central and west Africa, the second largest in the world, has been around for millions of years. However recent research suggests that it is mostly…Palm Oil Detectives

Thomas’s Langur Presbytis thomasi

Thomas’s Langur, also known as the North Sumatran Leaf #Monkey is famous for their bold facial stripes giving them a handsome profile. These monkeys are endemic to the lush forests of northern Suma…Palm Oil Detectives

PZ Cussons

PZ Cussons is a British-owned global retail giant. They own well-known supermarket brands in personal care, cleaning, household goods and toiletries categories, such as Imperial Leather, Morning Fr…Palm Oil Detectives

Blue-streaked Lory Eos reticulata

Brilliantly coloured and full of energy, the Blue-streaked Lory (Eos reticulata) is a striking and unique #parrot living in the forests of the Banda Sea Islands, #Indonesia. Their scarlet plumage i…Palm Oil Detectives

Sunda Clouded Leopard Neofelis diardi

Gliding through the rainforest canopy like a phantom predator, the Sunda Clouded Leopard moves with unmatched grace, making them one of the least understood big cats in the world. Their spectacular…Palm Oil Detectives

Declining primate numbers are threatening Brazil’s Atlantic forest

#Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, is facing severe threats due to deforestation and habitat fragmentation. This has led to a sharp decline in prim…Palm Oil Detectives

Sambar deer Rusa unicolor

The majestic Sambar deer, cloaked in hues ranging from light brown to dark gray, are distinguished by their rugged antlers and uniquely long tails. Adorned with a coat of coarse hair and marked by …Palm Oil Detectives

Meat-Stinking Giant Flower Has A Delectable Aroma For Pollinators

Meat-Stinking Giant Flower Has A Delectable Aroma For Pollinators